Photo AI

Last Updated Sep 26, 2025

Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage Simplified Revision Notes for A-Level Edexcel History

Revision notes with simplified explanations to understand Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage quickly and effectively.

281+ students studying

Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

What you need to know - Government Court, Privy Council and ministers, including the role and influence of William Cecil, Elizabeth's use and management of faction, role of gender, roles of the House of Commons and Lords, Parliament's relationship with the Queen, issues of marriage, succession and parliamentary privilege, the impact of marriage and succession on domestic and foreign affairs

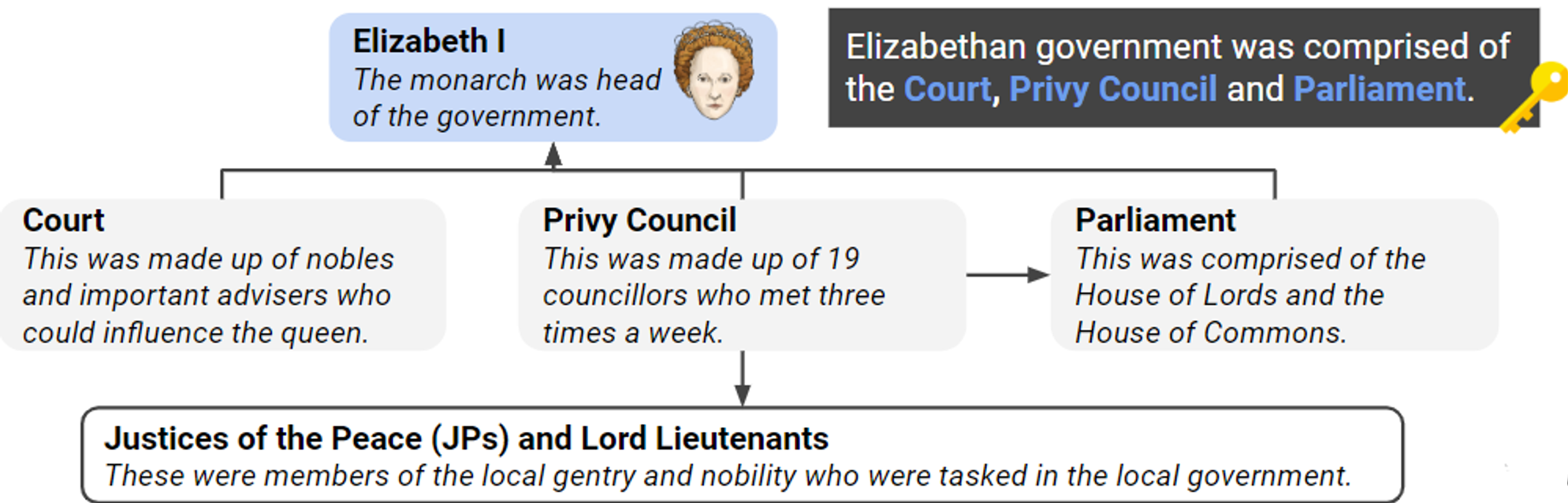

Elizabeth I's Government

Unlike her predecessor, Elizabeth as Queen Regnant exercised much more control over government, probably due to the difference in their character. She appeared to be a politique who was prepared to listen to her councillors' advice and compromise for long-term goals.

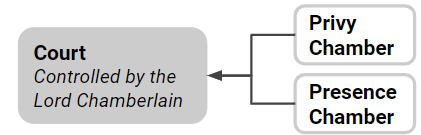

Court

- The court consisted of nobles, lawyers and higher gentry.

- It was the centre of royal power.

- However, courtiers had no authority; their role was to entertain and advise the monarch.

- In true patronage style, Elizabeth's favourite courtiers stayed in the same residence as her, others had to find lodgings nearby, and those who displeased her were sent away from court.

The court had no defined set of functions in the system of government but Elizabeth used it to govern England:

- The Queen used the court to obtain information.

- Whilst the Secretary of State was tasked with controlling the correspondence to the Queen, it was the Lord Chamberlain who controlled access to the Queen in court.

- Court was the centre of the patronage and faction system.

- In practice, a faction in the court helped the Queen dominate the Council.

- Court came in very useful for establishing the Cult of Gloriana

Elizabeth I was known as Gloriana, which means 'glorious woman', and was named after the heroine of Edmund Spenser's poem 'The Faerie Queene'.

The Queen could appoint whoever she wished to aid her in ruling the country and usually chose from the nobility. She used the court to show her wealth and power and hosted elaborate entertainment. Additionally, patronage was used to secure loyalty and maintain her control of English land as the nobility often had large armies.

During Elizabeth's reign, the Presence Chamber, a room in which a monarch or other distinguished person received visitors, grew in importance.

Patronage

Patronage is the power to control appointments to office or the right to privileges in exchange for loyalty. Where patronage occurs, appointments are not always based on ability (meritocracy), but on connections, favours, friendship and reward.

Different Types of Patronage

- Financial rewards that cost the Crown: pensions, gratuities and annuities; wardship of Crown lands

- Financial rewards that did not cost the Crown: custom farms, monopolies

- Employment: offices in the legal system and the local administration; positions in the armed forces; positions in the Church

- Non-Financial Patronage: court honours, knighthoods, peerages

The Privy Council

The Privy Council consisted of powerful noblemen appointed by Elizabeth I.

Its role was:

- To advise on foreign and domestic affairs, threats and challenges, war, relations with ambassadors, etc.

- To carry out political decisions, approved by the Queen

- To coordinate with JPs to keep in touch with the nation

A painting depicting Elizabeth's Privy Council

- Elizabeth manipulated her councillors when need be, but they too manipulated her when needed.

- She welcomed different perspectives and allowed members of the court to be heard, which kept factions appeased.

- During Elizabeth's reign, the post of the Secretary of State became more important.

- William Cecil was appointed to the post in 1558.

Key members of the Privy Council

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

- Secretary of State

- Privy Councillor for 40 years

- A Moderate Protestant concerned by the Catholic threat

- Would challenge her by using Parliament and courtiers to change her mind

- Elizabeth resented him after Mary, Queen of Scots execution

Sir Francis Walsingham

- Head of Secret Service

- Advised on foreign affairs

- A devout Puritan and worried about the Catholic threat

- Cold, calculating, straight-talking

- Uncovered the plot that led to Mary, Queen of Scots execution

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

- A trusted adviser of Elizabeth I until he died in 1588

- A Puritan who often butted heads with Cecil

- Would give conflicting advice to Cecil's

- Was very close with the Queen and many considered them lovers

Sir Christopher Hatton

- A moderate Protestant

- Appointed Lord Chancellor in 1587

- Became very wealthy as a result of the Queen's fondness for him

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

- Politically ambitious and committed

- A favourite of the Queen

- Often argued with her

- Played a part in an attempt to remove some of the Queen's councillors

- Rebelled in 1601 and was executed for treason

Role and Influence of William Cecil

The Secretary of State was Elizabeth's most important adviser, a post personally appointed by the Queen. Its duties were numerous and varied and not without dangers. The post was held by Sir William Cecil, Sir Thomas Smith, Sir Francis Walsingham, Thomas Wilson, William Davison and Sir Robert Cecil. Out of all Elizabeth's secretaries, Sir William Cecil was the most successful and influential.

Cecil was loyal to the Queen and their close relationship lasted until the Queen's death.

- He knew how to manage and persuade Elizabeth to change her mind.

Cecil presiding over the Court of Wards

- During Elizabeth's reign, he was appointed to important positions in the government such as Lord Treasurer, Lord Privy Seal and JP, which allowed him to influence events in Parliament and the Council. He also aided the Queen's political patronage system.

- Whilst he was a committed Protestant who supported the tightening of controls on English Catholics, he was known to have a difficult relationship with another favourite of Elizabeth, the more radical Puritan Robert Dudley.

Elizabeth's Use and Management of Faction

The formation of rival factions by the members of the Privy Council was inevitable. However, Elizabeth I used this to her advantage by forcing her councillors to work together to come up with informed decisions. Her councillors would give contrasting advice and, consequently, whichever course of action she would choose would have backing. Grounds of differences between the members of the Council included religion, foreign policy issues and the Queen's marriage. Rivalry coupled with competition for the Queen's affection could be beneficial to the government.

There were three main rival factions in Elizabeth's reign.

Early 1560s: Early of Sussex vs Earl of Leicester

This rivalry got out of hand and could have gotten worse if Elizabeth had not forced the two to reconcile. Leicester attempted to get Sussex convicted of misconduct over his work in Ireland whilst Sussex tried to prove that Leicester had murdered his wife. The faction from each side carried weapons and wore party colours.

Late 1560s: William Cecil vs Earl of Leicester

This rivalry was rooted in Leicester's intention to marry the Queen and his resentment towards Cecil's influence. Cecil was not supportive of Leicester's intention. Soon they clashed, with Leicester trying and failing to get Cecil dismissed. However, the conflict between them was resolved later and did not affect the government that much.

Late 1590s: Robert Cecil vs The Earl of Essex

This rivalry was the most serious of all as it somehow contributed to the Essex Rebellion in 1601. Robert Cecil looked to fill his father's position whilst Essex looked to replace his stepfather (Leicester). As both of them were placed in important positions in the Council, they competed with each other like their predecessors. As matters got worse, Essex was banned from Court which weakened his faction. He planned a rebellion that led to his execution.

Parliament

Parliament had two constituent parts: the House of Lords (90 peers) and the House of Commons (450 elected MPs). The Lords were made up of the nobility and bishops whilst the Commons was made up of educated gentry, lawyers and merchants voted in by landowners and wealthy citizens.

- Parliament could only meet if Elizabeth called it, set the agenda and followed the allowed discussion.

- It met only 13 times in her 45-year reign.

- Elizabeth mainly used Parliament to grant her taxes - this was her main income.

- Although the subject of marriage and having children became strictly off-limits, the Commons brought up these issues several times which led to tensions in Parliament.

The role of Parliament remained the same in Elizabeth I's reign:

- To grant extraordinary taxation when the monarch needed money.

- To pass laws and Acts of Parliament

Etching depicting Elizabeth in Parliament

By 1558, the changes brought by Henry VIII and the English Reformation began to bear fruit in Parliament. Parliament was granted significant power during Henry VIII's reign as it worked side by side with the monarch. This continued through to the succeeding Tudor monarchs. By the time of Elizabeth's reign, the MPs became increasingly confident to raise issues that the Queen forbade. The Queen limited freedom of speech in Parliament. However, the Council was sometimes forced to compromise to resolve the parliamentary conflict. Nevertheless, Elizabeth had the right to block measures proposed by MPs by using the royal veto.

What did Parliament accomplish in Elizabeth I's reign?

- 1559 Royal supremacy over the Protestant Church of England was restored.

- 1563 Taxes to fund wars against Scotland and France were approved.

- 1566 Parliament agreed to fund an army to be sent to France.

- 1571 Laws against the Pope and traitors passed. Taxes were granted to defeat rebellion in the North.

- 1572 After the discovery of the Catholic plot, Parliament discussed the Queen's safety.

- 1576 Even though the country was at peace, MPs agreed to taxes being enacted.

- 1581 Anti-Catholic laws were passed. Taxes were approved to fund an army to be sent to Ireland.

- 1584-5 More laws against Catholic priests were passed. More taxes were requested and granted.

- 1586-7 Parliament granted taxes for going to war with Spain.

- 1589 The costs of defeating the Spanish Armada the year prior demanded taxes. They were granted.

- 1593 More anti-Catholic laws were passed. More taxes were needed for a war with Spain.

- 1597-8 Laws passed regarding the poor and more taxes were granted.

- 1601 Taxes passed to pay for the army in Ireland. More taxes were granted to fund the war with Spain.

Parliamentary Privilege

Parliament became increasingly significant in the Tudor government and concerns over rights and privileges of MPs became evident in Elizabeth's reign.

Certain privileges of MPs included

- They could not be arrested for debt.

- They could not be prosecuted in lesser law courts.

- They could speak freely within the Commons chamber. However, Parliamentary managers appointed by the monarch could relay the contents of discussions made in the chamber, which could result in tension between Parliament and the monarch. MPs believed that they had the right to be heard on issues relating to the Queen's marriage, succession and religion. With the aid of the Queen's trusted councillors, Elizabeth suppressed these debates. However, one MP managed to challenge the Queen:

Peter Wentworth

He was a prominent Puritan leader who attacked royal parliamentary management and defended the MPs' right to freedom of speech. He wanted to make changes to the religious laws, a topic banned by Elizabeth. He was imprisoned for a month for his outburst.

This incident demonstrated the increased confidence of the Commons, which meant that the Commons had to be managed carefully.

Role of Gender

- Rising to the throne as a young woman in a patriarchal society, Elizabeth faced considerable prejudice.

- Women were thought to be weak, intellectually inferior and lacked the desired masculine temperament to handle politics such as assertiveness and decisiveness.

- It was feared that a weak monarch would bring chaos, as with the War of the Roses.

- Furthermore, it did not help that Mary I's short reign caused discontent and fear in England due to her policies and unpopular marriage.

- Though Elizabeth was young, beautiful and Protestant, her accession was welcomed as much for these qualities as plain relief that Mary's tyrannical reign had ended. The rule of a woman in her own right was regarded as unnatural during this period. However, Elizabeth successfully turned the issue of her gender into her advantage. She defined her femininity as beneficial to the safety of the realm.

- Elizabeth asserted that her accession was the result of God's will and not her ambition, stressing her divine right.

- Elizabeth depicted her femininity in a desirable light, not to be perceived as a threat to the established male hierarchy.

- Elizabeth drew on her femininity to evoke loyalty from her subjects by considering marriage and entertaining courtship from her courtiers and foreign suitors.

- Elizabeth nurtured a maternal relationship with Parliament, transforming herself from England's Virgin Queen to England's Virgin Protector, Gloriana. The Queen resolved the questions surrounding her femininity. In her long reign, it can be said that her gender became her strength.

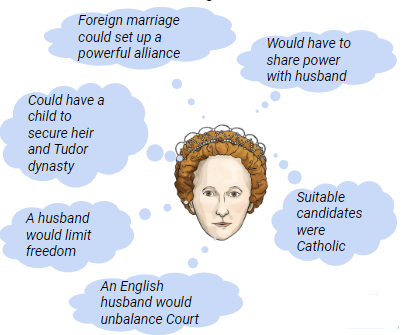

Elizabeth I and Marriage

Like the Queen Regnant before her, Elizabeth's rule was surrounded by issues of her gender, marriage and heir. There was extra pressure on Elizabeth as she was the last of the Tudor dynasty. Elizabeth had many suitors throughout her life but ultimately refused to give up sole sovereignty of England and never married.

Elizabeth I's Suitors

1530s-40s

1534 Duke of Angouleme (3rd son of Francis I)

1544 Philip II of Spain (Mary's widow)

1547 Sir Thomas Seymour

1550s

1553 Edward Courtenay

1554 Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy

1554 Prince Frederick of Denmark

1556 Prince Eric of Sweden

1556 Don Carlos (son of Philip II)

1559 Philip II (again)

1559 Sir William Pickering

1559 James Hamilton, Earl of Arran

1559 Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

1559 Lord Robert Dudley

1560s

1560 King Eric XVI of Sweden

1560 Duke of Holstein

1560 King Charles IX of France

1560 Henry de Valois, Duke of Anjou

1563 Lord Darnley

1568 Archduke Charles of Austria

1570s

1570 Henry Duke of Anjou

1572 Francois, Duke of Alencon later Anjou

(20 years Elizabeth's junior, he was short, scarred by smallpox and Elizabeth affectionately called him her 'frog'.)

Issues of Marriage

When Elizabeth was considering marriage, she faced dilemmas in choosing a suitable husband.

Out of all the Queen's suitors, she considered marriage twice:

- Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester: He was a favourite of the Queen and a long-term suitor although married already. However, the match was disliked by many especially when his wife died in suspicious circumstances.

- Francis, Duke of Anjou: He was a Catholic and his union with the Queen would come with political benefits. The Queen was attracted to him. However, negotiations were called off.

Elizabeth remained single for the rest of her reign and declared that she was married to her kingdom.

Issues of Succession

The issue of succession followed Elizabeth I. From the start, Catholics questioned her legitimacy. She had refused to marry (meaning any children would be illegitimate - and scandalous), and in 1562, Elizabeth contracted smallpox and nearly died. Had she died, there would have been a serious succession crisis.

Elizabeth's Stance

After she recovered, Parliament pressured her to marry or nominate an heir. Her character being what it was, she refused to do both. She claimed she would marry when the time was right and that prematurely nominating an heir would place her life in danger.

The Small Matter of Surplus

With no further Tudor heirs, the Stuarts and Suffolks could lay claim. Henry VIII's will stated his sister Mary, Duchess of Suffolk, could become queen. Her granddaughter Lady Jane Grey stepped up as queen for 9 days before Mary I had her deposed. Two Protestant Greys remained, Catherine and Mary. On a technicality, however, Elizabeth's Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, had a stronger claim.

The Issue of Mary, Queen of Scots

Elizabeth's attempt to bring Mary, Queen of Scots under English influence failed. Mary rejected the Queen's suggested husband and married Lord Darnley (Henry Stuart) instead. This marriage strengthened the Stuart claim and the birth of their child James was viewed as an advantage.

500K+ Students Use These Powerful Tools to Master Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage For their A-Level Exams.

Enhance your understanding with flashcards, quizzes, and exams—designed to help you grasp key concepts, reinforce learning, and master any topic with confidence!

470 flashcards

Flashcards on Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

Revise key concepts with interactive flashcards.

Try History Flashcards32 quizzes

Quizzes on Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

Test your knowledge with fun and engaging quizzes.

Try History Quizzes29 questions

Exam questions on Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

Boost your confidence with real exam questions.

Try History Questions27 exams created

Exam Builder on Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

Create custom exams across topics for better practice!

Try History exam builder120 papers

Past Papers on Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage

Practice past papers to reinforce exam experience.

Try History Past PapersOther Revision Notes related to Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage you should explore

Discover More Revision Notes Related to Elizabeth I: Government, Ministers and Marriage to Deepen Your Understanding and Improve Your Mastery

96%

114 rated

Elizabethan England, 1558-1603

Elizabeth I: Character, Accession, and Reign

466+ studying

194KViews96%

114 rated

Elizabethan England, 1558-1603

Mary Queen of Scots, Plots and Succession

353+ studying

186KViews96%

114 rated

Elizabethan England, 1558-1603

The Religious Situation under Elizabeth I: Domestic and Abroad

423+ studying

188KViews96%

114 rated

Elizabethan England, 1558-1603

Golden Age and English Renaissance

255+ studying

197KViews