Photo AI

Last Updated Sep 26, 2025

The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade Simplified Revision Notes for A-Level Edexcel History

Revision notes with simplified explanations to understand The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade quickly and effectively.

333+ students studying

The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

What you need to know - The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade: the significance of the death of Frederick Barbarossa; the rivalries of Richard I and Philip II; Richard's decision to attack Sicily and Cyprus; Philip's return to France. Richard's leadership at Acre and Jaffa and reasons for his decision not to attack Jerusalem.

Following the capture of Jerusalem by Sultan Saladin in 1187, the Third Crusade was called by Gregory VIII. It was participated in by three kings - Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire, Philip II of France, and Richard I of England. Historians suggest that the Third Crusade was partially successful in recapturing Acre and Jaffa Sicily and Cyprus but failed to seize Jerusalem, the centre of the Holy Land.

Frederick I (Barbarossa) (1155-1190)

Elected as King of Germany in 1152, crowned as King of Italy and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in 1155

Richard I of England (1189-1199)

3rd of the 5 sons of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Philip II of France

(1190-1223)

Son of Louis VII to his 3rd wife, Adela of Champagne. He ended the Angevin Empire.

Death of Frederick Barbarossa

On 1 December 1187, Bishop Henry of Strasbourg preached before Frederick I about the Third Crusade. Unsure of participating, Frederick I met with his ally, Philip II of France. However, Philip was reluctant to join the crusade because he was at war with England. Following the diet in Mainz in March 1188, Frederick I took the cross after the crusade sermon of Bishop Godfrey of Würzburg. He was supported by his son, Frederick VI of Swabia, and by Frederick of Bohemia and Leopold V of Austria.

Frederick I crossing the river

Based on the History of the Expedition of the Emperor Frederick and the History of the Pilgrims, Frederick I's crusade was well-planned.

At the time of the Third Crusade, Frederick I was 66 years old.

Contemporary estimates suggest that Frederick I's army was composed of 12,000 to 15,000 men on foot and 2,000 to 4,000 knights when they set out on 11 May 1189.

Before reaching the Byzantine territory, Frederick and his crusading army passed through Hungary, Serbia and Bulgaria. In Hungary, he convinced Prince Géza and about 2,000 men to join the crusade. By the autumn of 1189, Frederick's army camped in Adrianople. In March 1190, he sailed from Gallipoli at the Dardanelles towards Asia Minor. Frederick's army won at the Battle of Iconium, a result that concerned Saladin. While traversing the Saleph River, Frederick died of drowning on 10 June 1190.

Following his death, the majority of the German soldiers left the crusading army and returned home. The remaining army was further weakened by the weather and disease they faced near Antioch.

Frederick I depicted in the Third Crusade

A Gotha manuscript depicting Frederick I drowning

The remnants of the remaining German-Hungarian army were carried on by Frederick VI of Swabia and Prince Géza. Only a third of the original force arrived in Acre.

Rivalries of Richard I and Philip II

According to Sir Steven Runciman, an English medievalist, Philip II of France was six years younger than Richard I but had been a king for eight years more than the latter. At the age of 24, Philip II took the cross in January 1188. At that time, England was ruled by Henry II, the father of Richard. At the sermon of Archbishop Joscius of Tyre, Philip II and Henry II set aside their differences and decided to join the crusade. To distinguish their respective armies during the crusade, the English wore white, while the French wore red. In 1189, the rivalry between the French and Angevin king was renewed when Richard ascended the English crown. Richard was Philip's vassal due to his lands in France, including Normandy, Aquitaine and Anjou. Richard had larger, more organised and better-equipped soldiers than the French. Due to tension and mistrust, both crusading armies assured that they would leave Europe at the same time.

9th-century paintings of (left) Philip II of France and (right) Richard I of England

Despite having less experience than Philip as king, Richard was decisive in warfare. Accounts also described Richard as physically more superb than the French king.

At the age of fifteen, Richard became the Duke of Aquitaine. Aquitaine is located in south-western France and was part of Henry II's Angevin Empire. Historians suggest that Richard I's prompt response to the Third Crusade was because of his lineage and great religious devotion. Richard was the great-grandson of Fulk of Anjou, King of Jerusalem between 1131 and 1142. In order to fund the crusade, Richard I imposed a special crusading tax known as 'Saladin's Tithe'. Furthermore, he sold an enormous amount of land and property to make sure that the crusading army was well-funded.

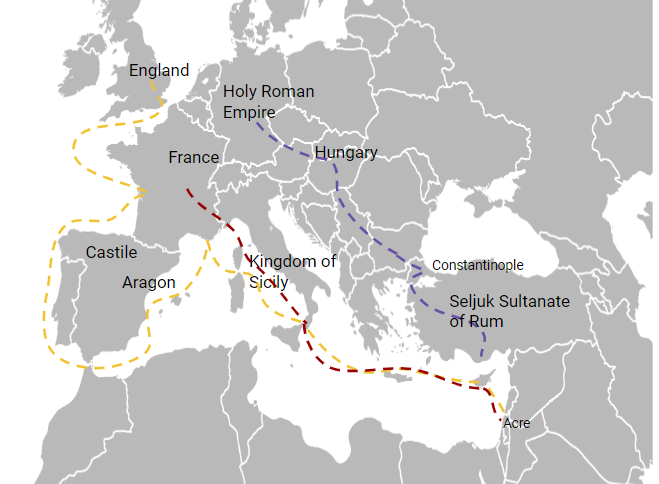

Map showing the routes of Frederick I, Philip II and Richard I during the Third Crusade

Richard in Sicily and Cyprus

In 1189, Tancred, cousin of the deceased William II of Sicily, seized power. Tancred imprisoned Queen Joan, William II's widow, and Richard I's sister, to secure his power. When Richard I and Philip II arrived in Sicily in September 1190, the former demanded his sister's release and inheritance. Before the end of September, Queen Joan was released but without inheritance. By the following month, internal unrest in Sicily erupted. The people of Messina demanded the foreigners to leave. In response, Richard I attacked, looted and established a headquarters in Messina. This attack by Richard I created tensions between Philip II.

On 4 March 1191, Tancred agreed to sign a treaty under the given terms:

French manuscripts showing Richard I and Philip II

1 Queen Joan will receive 20,000 ounces of gold as inheritance

2 Richard I named his nephew, Arthur of Brittany as his heir. Tancred betrothed one of his daughters to Arthur. In case Arthur fails to marry, he will give 20,000 ounces of gold to Tancred.

While in Sicily, Philip II plotted with Tancred against Richard I. This tension ended with an agreement that included Richard's marriage to Alys, Philip II's sister.

In May 1191, Richard I anchored on the south coast of Cyprus to meet his sister and another fiancée, Berengaria of Navarre, the daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre. While in Cyprus, Richard I received the support of several princes of the Holy Land, including Guy of Lusignan. Cyprus was then ruled by Isaac Komnenos, who fell out of favour from the local magnates. By June, Richard I and Guy Lusignan conquered the island. Cyprus was a strategic location for sailors going to the Holy Land.

Richard I's marriage to Berengaria of Navarre at Cyprus

Despite his accidental conquest of Cyprus, Richard I's invasion of this island became one of the central themes of his heroic journeys in popular culture. It is said that Richard I's motivation in invading Cyprus was Isaac's maltreatment of English shipwreck survivors. From being a passerby, he became the ruler of Cyprus. Richard's troops ransacked the wealth of the city to fund the crusade.

Philip's return to France

On 20 April 1191, Philip II's crusading army arrived at Acre. Even before Philip's arrival, Acre was already under siege. By the time Acre fell through the crusaders, Philip II was suffering from dysentery. Despite the crusaders' victory, the siege of Acre resulted in Philip's death, Count of Flanders. His death resulted in a succession crisis in Flanders which urged Philip II to return to France.

It is believed that Philip II's decision to return home further strained his relationship with Richard I. Richard I viewed his action as a shame and a disgrace.

Philip (centre) and King Richard I of England accepting the keys to Acre (illumination on parchment, c. 1375-1380)

Philip II and his cousin, Peter of Courtenay, Count of Nevers, returned to France through Rome. Some also believed that Philip I's decision was also due to the absence of Richard I to protect northern France. Richard I's participation in the crusade left his duchies in France unattended. Moreover, Richard I's marriage to Berengaria broke his initial betrothal to Alys, Philip II's sister.

Before returning to France, Philip II requested Pope Celestine III in Rome to release him from his oath not to attack Richard I's territories. Celestine III declined. As a result, Philip II began plotting. On 20 January 1192, he presented a fake document to Richard II's seneschal of Normandy, William FitzRalph. The document presented a supposed agreement between Richard I and Philip II at Messina regarding the handover of Vexin. Similar to Philip II's plea to the pope, his deception led to no avail.

An illumination from a 14th-century CE manuscript of the 'Grandes Chroniques de France', depicting King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE) paying homage to Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223 CE).

Philip II also circulated stories that Richard I made a secret alliance with Saladin and participated in the murder of Conrad of Montferrat. Lastly, Philip II forced a conspiracy with Richard I's brother, John.

In 1193, John began paying homage to Philip II in Paris. By the time Richard I was held captive on his way home from the crusade, Philip II immediately ordered attacks in Gisors, Dieppe and Rouen.

Richard's leadership at Acre and Jaffa and reasons for his decision not to attack Jerusalem

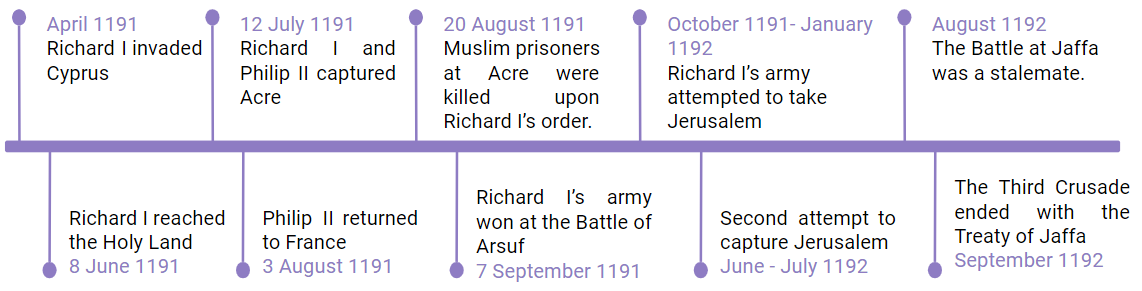

A brief timeline of significant events upon Richard I's arrival in the Holy Land

On 8 June 1191, Richard's army arrived at Acre. According to chroniclers, Richard I was sick with Arnaldia, a similar disease to scurvy. However, despite his poor health, Richard I attempted to use diplomacy in negotiating with Saladin. Unfortunately, it did not work. In late June, the siege of Acre heightened with catapults and sappers. By 12 July, Saladin's forces surrendered Acre.

Following the Muslim defeat, Acre's property was divided between Richard I and Philip II. Tensions between the two arose again because they supported different claimants to Jerusalem's throne. Richard I supported Guy of Lusignan, while Philip II chose Conrad of Montferrat.

Despite Saladin's defeat, the Muslim ruler refused to hand over the True Cross and release French prisoners. As a result, Richard I ordered the murder of all Muslim prisoners at Acre, apart from significant people who could be ransomed. Richard I's brutality sent a clear message to Saladin.

Depiction of about 2,700 Muslim prisoners executed at Acre, in August 1191

After the Crusaders' victory at Acre, Richard I decided to attack Jaffa instead of Jerusalem. It is suggested that Richard I's plan was to capture Jaffa followed by the coastal city of Ascalon to cut Saladin's trade route to Egypt. On 22 August, Richard I assembled about 15,000 troops to continue the campaign.

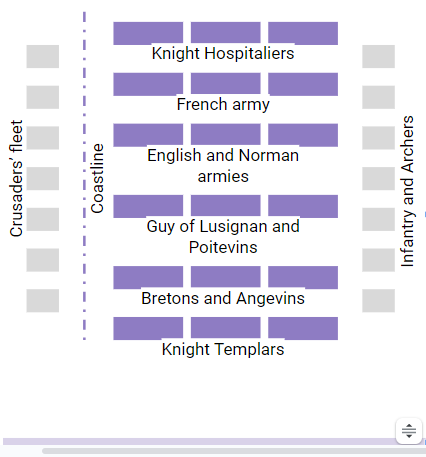

Formation of the crusading army

The diagram shows that the knights of the Hospitalier and Templars were positioned at the front and rear. With mounted knights, Richard I was positioned in the middle. The army was protected by infantry and archers on the left, while the Crusaders' fleet was on the coast to provide necessary supplies.

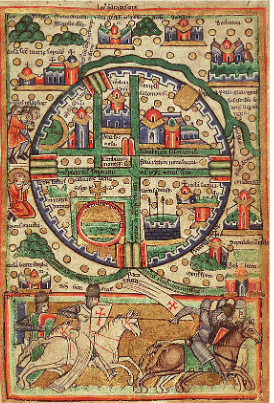

Map of the Holy Land in 1191-1192

To survive the scorching heat at Jaffa, Richard I allowed his troops to rest and prevented fights over food.

On 7 September 1191, while the crusading army was only 25 miles away from Jaffa, Saladin launched a surprise attack. Saladin's 30,000 men were composed of mounted and on-foot warriors. In response, Richard I ordered his army not to break their formation. With forceful counterattacks and renewed charges, the crusading army pushed Saladin's forces to retreat.

Depiction of the Battle of Arsuf

After capturing Jaffa, Richard I insisted on attacking Ascalon. However, the majority of nobles were persistent in taking Jerusalem. While the Crusaders were divided, Saladin sacrificed Ascalon and decided to take down Crusader castles between Jaffa and Jerusalem. On 29 October 1191, the Crusaders began to rebuild Crusader forts but were repeatedly attacked by Saladin's troops.

According to historian Thomas Asbridge, Richard I's leadership at Arsuf was significant but is often exaggerated by contemporary historians. He agreed that the Battle of Arsuf was a critical turning point in the Third Crusade. The result boosted the morale of the crusading army.

What happened after the attack?

On 13 January 1192, Richard I ordered the retreat of the crusading army to Ascalon. In the spring of 1192, pressures within and outside Jerusalem led to divided leadership. Conrad of Montferrat challenged the authority of Guy of Lusignan and allied with other nobles. With the overwhelming support for Conrad, Richard I abandoned Guy and switched his support. However, Conrad was killed at Tyre on 28 April.

Despite the attacks, Richard I ventured into diplomacy. He negotiated with al-Adil, Saladin's brother, to divide Palestine. Richard I even offered his sister, Joan, to be one of al-Adil's wives. When the winter set, the crusading army was still twelve miles from Jerusalem. At this time, Richard I was doubtful if their supply lines could still support the siege of Jerusalem. Moreover, he believed that even if they succeeded in capturing the city, they had insufficient manpower to protect it.

Historians suggest that the impact of Frederick I's death and Philip II's return to France were massively felt during this time.

Marriage of Conrad of Montferrat and Isabella of Jerusalem

Conrad of Montferrat was an Italian noble who became the de facto king of Jerusalem in 1190 upon his marriage to Isabella I. In 1192, Conrad I was officially elected as king.

In May 1192, news from Europe reached Richard I. He learned that his brother, John, conspired with Philip II and exiled his viceroy, William Longchamp. Richard I's mind was divided by news from home and the nobles' insistence on capturing Jerusalem. On 10 June, the Crusaders reached Beit Nuba. On their way to Jerusalem, they attacked a Muslim caravan. However, the Crusaders' vulnerable supplies, similar to Jaffa, lack of water, and Jerusalem's great fortifications convinced Richard I and most Crusaders to retreat. Only the French army was eager to continue. By 4 June, the Third Crusade ended.

Manuscript showing the Siege of Acre

Depiction of Saladin's troops

Plan of Jerusalem, 1200

500K+ Students Use These Powerful Tools to Master The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade For their A-Level Exams.

Enhance your understanding with flashcards, quizzes, and exams—designed to help you grasp key concepts, reinforce learning, and master any topic with confidence!

220 flashcards

Flashcards on The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

Revise key concepts with interactive flashcards.

Try History Flashcards17 quizzes

Quizzes on The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

Test your knowledge with fun and engaging quizzes.

Try History Quizzes29 questions

Exam questions on The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

Boost your confidence with real exam questions.

Try History Questions27 exams created

Exam Builder on The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

Create custom exams across topics for better practice!

Try History exam builder120 papers

Past Papers on The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade

Practice past papers to reinforce exam experience.

Try History Past PapersOther Revision Notes related to The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade you should explore

Discover More Revision Notes Related to The troubled leadership of the Third Crusade to Deepen Your Understanding and Improve Your Mastery

96%

114 rated

Leadership of the Crusades, 1095-1204

Louis VII, Conrad III and the Second Crusade

205+ studying

192KViews96%

114 rated

Leadership of the Crusades, 1095-1204

Significance of the failure of Prince Alexius and of the sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade

233+ studying

184KViews