Photo AI

Last Updated Sep 26, 2025

Monopoly Simplified Revision Notes for A-Level Edexcel Economics A

Revision notes with simplified explanations to understand Monopoly quickly and effectively.

257+ students studying

4.2 Monopoly

DEFINITIONS:

- Monopoly: A monopoly is a market structure where a single firm is the sole seller of a product or service with no close substitutes, allowing it to control market prices and output.

- Dynamic efficiency: Dynamic efficiency occurs when a firm is able to improve its productive efficiency over time through investment in innovation, research and development, and new technologies.

- X-inefficiency: X-inefficiency occurs when a firm produces output at a higher cost than necessary due to a lack of competitive pressure, resulting in wasteful production practices.

- Supernormal profit in both short and long run: Supernormal profit, also known as economic profit, occurs when a firm's total revenue exceeds its total costs, including both explicit and implicit costs, and can persist in both the short and long run in a monopoly due to barriers to entry.

- Productive and allocative efficiency with a profit-maximising monopolist: A profit-maximising monopolist is generally neither productively efficient, as it does not produce at the lowest possible average cost, nor allocatively efficient, as it sets a price above marginal cost, leading to underproduction and a welfare loss.

- Price discrimination by a firm with monopoly power: Price discrimination by a monopolist involves charging different prices to different consumers for the same product or service, based on their willingness to pay, in order to maximize profits.

- Natural monopoly: A natural monopoly exists when a single firm can supply the entire market's demand for a good or service at a lower cost than any combination of two or more firms, due to significant economies of scale.

Explain:

4.2.1 The characteristics of monopoly

The characteristics of a monopoly can be summarized as follows:

- Single Seller: A monopoly exists when there is only one firm in the market, meaning the firm is the sole producer or provider of a good or service.

- Unique Product: The product offered by the monopoly has no close substitutes, which means consumers cannot easily switch to a different product if the monopolist raises prices.

- High Barriers to Entry: Significant barriers prevent other firms from entering the market. These can be legal (e.g., patents), natural (e.g., control of a key resource), or economic (e.g., economies of scale).

- Price Maker: A monopolist has significant control over the price of its product because it is the only supplier. Unlike in competitive markets, a monopolist can influence the market price by altering the quantity it supplies.

- Profit Maximization: The monopolist will aim to maximize profits where marginal revenue (MR) equals marginal cost (MC). This typically results in higher prices and lower output compared to competitive markets.

- Potential for Supernormal Profits: Due to lack of competition and barriers to entry, a monopolist can earn supernormal (or abnormal) profits in the long run.

- Inefficiencies: Monopolies can lead to allocative and productive inefficiencies. Allocative inefficiency occurs because the monopolist sets a higher price and lower output than in a competitive market, leading to a loss of consumer and producer surplus (deadweight loss). Productive inefficiency arises because a monopolist might not produce at the lowest possible cost. Understanding these characteristics helps in analyzing the impact of monopolies on consumer welfare, market efficiency, and economic policies.

4.2.2 Dynamic efficiency

Dynamic efficiency refers to the ability of an economy to improve the range and quality of products over time, as well as to enhance production processes. It encompasses the concept of innovation, technological progress, and the development of new products and services. In the context of dynamic efficiency, firms are incentivized to invest in research and development (R&D) to create new and better products, reduce costs, and improve their production techniques. This continual improvement leads to long-term growth and increases in consumer welfare. Dynamic efficiency contrasts with static efficiency, which focuses on the optimal allocation of resources at a particular point in time. By emphasizing long-term improvements and adaptations, dynamic efficiency ensures that an economy can respond to changing consumer preferences and technological advancements.

4.2.3 X-inefficiency

X-inefficiency refers to a situation where a firm is not operating at its lowest possible cost due to a lack of competitive pressure. This often happens in markets where there is a monopoly or limited competition, allowing firms to become complacent and inefficient in their operations. X-inefficiency can arise from poor management, lack of motivation among employees, wasteful practices, or failure to adopt new technologies.

Key points include:

- Lack of Competition: In markets with little or no competition, firms may not have the incentive to minimize costs.

- Cost Inefficiencies: Firms incur higher production costs than necessary, leading to wasted resources.

- Organizational Slack: Management may not be stringent about cost controls, leading to inefficiencies.

- Examples: Overstaffing, bureaucratic processes, and outdated technology. In essence, X-inefficiency highlights the deviation from optimal production efficiency due to internal inefficiencies within the firm.

Explain With Aid of a Diagram

4.2.4 Monopoly

Explanation of Monopoly and Supernormal Profit

Monopoly: A monopoly exists when a single firm dominates the market for a particular good or service, facing no significant competition. This firm is the sole provider of the product and has significant control over its price.

Supernormal Profit: Supernormal profit (also known as abnormal or economic profit) occurs when a firm's total revenue exceeds its total costs, including both explicit and implicit costs. Monopolies can sustain supernormal profits in both the short run and the long run due to high barriers to entry that prevent other firms from entering the market.

Short Run and Long Run Supernormal Profit in Monopoly

Short Run:

In the short run, a monopoly maximizes profit by producing the quantity of output where marginal cost (MC) equals marginal revenue (MR). The price is determined by the demand curve at this quantity. The area between the average total cost (ATC) curve and the price line (P) over the quantity produced represents supernormal profit.

Long Run:

In the long run, the monopoly can continue to earn supernormal profits because high barriers to entry prevent new firms from entering the market and eroding these profits. The firm's cost curves may adjust, but the monopoly will still produce where MC equals MR and set a price based on the demand curve, maintaining supernormal profits.

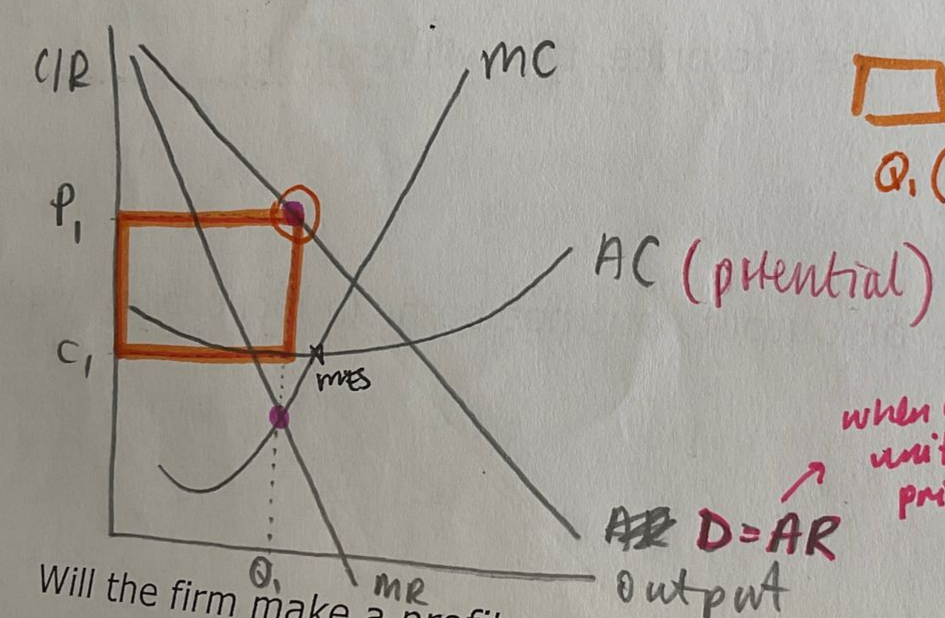

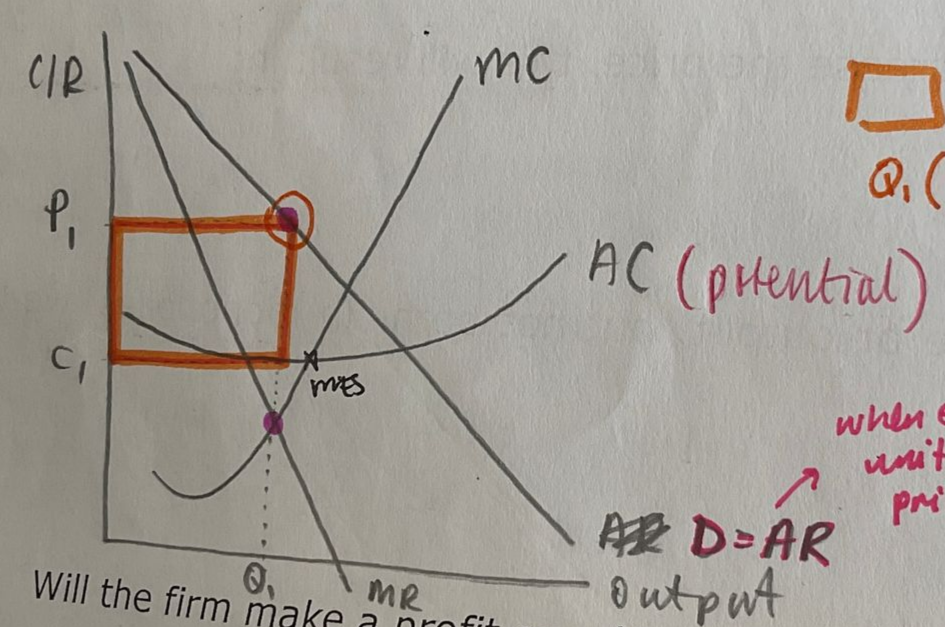

Diagram:

Below is a diagram illustrating a monopoly earning supernormal profit in both the short run and the long run:

Key Points in the Diagram:

- MC = MR: The monopoly maximizes profit by producing at the quantity where MC equals MR (Q*).

- Price Determination: The price (P*) is set based on the demand curve at the quantity Q*.

- Supernormal Profit: The area between the price (P*) and the ATC curve, above Q*, represents supernormal profit.

Summary:

- Short Run: The monopoly maximizes profit where MC = MR and charges a price based on the demand curve, earning supernormal profit.

- Long Run: Due to high barriers to entry, the monopoly continues to earn supernormal profits by maintaining the same profit-maximizing behavior. In both periods, the monopoly's ability to restrict output and set prices above competitive levels allows it to sustain supernormal profits.

4.2.5 Explanation of a Monopolist as a Price Maker

A monopolist is a single seller in a market with no close substitutes for its product. This unique position allows the monopolist to exercise significant control over the market price of its product. Unlike firms in perfect competition, which are price takers, a monopolist is a price maker. This means the monopolist can set the price by determining the quantity of the product it supplies.

Key Points:

- Market Power: The monopolist has significant market power because it is the sole provider of the good or service. This enables it to influence the price directly.

- Demand Curve: The monopolist faces a downward-sloping demand curve, meaning it can choose a combination of price and quantity where consumers are willing to buy.

- Profit Maximization: The monopolist maximizes profit where marginal cost (MC) equals marginal revenue (MR). The price is then determined by the demand curve at this quantity.

Profit Maximization:

Diagram Explanation:

- Demand Curve (D): Shows the relationship between price (P) and quantity demanded (Q). It slopes downward, indicating that a lower price increases quantity demanded.

- Marginal Revenue Curve (MR): Lies below the demand curve because to sell additional units, the monopolist must lower the price on all units sold.

- Marginal Cost Curve (MC): Represents the additional cost of producing one more unit. In a typical diagram, it slopes upward due to increasing marginal costs.

- Quantity (Qm): The monopolist chooses to produce quantity Qm where MR = MC.

- Price (Pm): The monopolist sets the price based on the demand curve at Qm.

- Profit Area: The area between the price (Pm) and the average cost curve (not shown here) up to the quantity Qm represents the monopolist's profit. In summary, a monopolist is a price maker because it can set the market price by choosing the quantity to produce, based on its unique position in the market and the downward-sloping demand curve it faces. This ability to influence price is a key characteristic of monopoly power.

4.2.6 Explanation of Equilibrium Price and Output for a Profit Maximizing Monopolist

A monopolist is a single seller in a market with significant barriers to entry, which allows it to set prices above marginal costs. The profit-maximizing output and price for a monopolist occur where marginal revenue (MR) equals marginal cost (MC).

Key Points:

- Demand Curve (D): Downward sloping, indicating that higher prices lead to lower quantities demanded.

- Marginal Revenue (MR) Curve: Lies below the demand curve because, to sell additional units, the monopolist must lower the price on all units sold.

- Marginal Cost (MC) Curve: Typically upward sloping, representing increasing costs with higher output.

- Profit Maximization Condition: Occurs where MR = MC.

Explanation with the Aid of a Diagram:

To better visualize:

- Locate the intersection of MR and MC to find Qm (the profit-maximizing output).

- Draw a vertical line from Qm up to the demand curve (D) to find Pm (the price consumers are willing to pay for Qm. This method ensures that the monopolist maximizes profit by equating marginal revenue with marginal cost and setting the price based on the demand curve.

4.2.7 Productive and Allocative Efficiency with a Profit Maximizing Monopolist

Productive Efficiency: Productive efficiency occurs when a firm produces at the lowest possible cost. This is achieved when production occurs at the minimum point of the average cost (AC) curve.

Allocative Efficiency: Allocative efficiency occurs when the price of a good equals the marginal cost (MC) of production. This ensures that resources are distributed in a way that maximizes consumer and producer surplus, meaning that the value consumers place on the good equals the cost of the resources used to produce it.

Monopolist's Behaviour:

A profit-maximizing monopolist will produce where marginal cost (MC) equals marginal revenue (MR), not where price equals marginal cost.

Explanation:

- Monopoly Equilibrium:

- A monopolist sets quantity (Qm) where MR = MC.

- The price (Pm) is set based on the demand curve (not shown but assumed to be above MR).

- Productive Efficiency:

- Productive efficiency occurs at the minimum point of the AC curve. In a monopoly, the quantity produced (Qm) is usually less than the quantity where AC is minimized, meaning the monopolist is not productively efficient.

- Allocative Efficiency:

- Allocative efficiency occurs where P = MC. In a monopoly, the price (Pm) is higher than MC at the profit-maximizing quantity (Qm), meaning the monopolist is not allocatively efficient.

4.2.8 Price Discrimination by a Firm with Monopoly Power

Definition: Price discrimination occurs when a firm sells the same product or service at different prices to different consumers, not based on differences in costs. A firm with monopoly power can engage in price discrimination to maximize profits by capturing consumer surplus.

Types of Price Discrimination:

- First-Degree (Perfect) Price Discrimination: Charging each consumer the maximum price they are willing to pay.

- Second-Degree Price Discrimination: Charging different prices based on the quantity consumed or the version of the product.

- Third-Degree Price Discrimination: Charging different prices to different groups of consumers based on their elasticity of demand (e.g., student discounts, senior citizen discounts).

Conditions for Price Discrimination:

- Market Power: The firm must have some control over prices (monopoly power).

- Market Segmentation: The firm must be able to segment the market and identify different groups of consumers with varying price elasticities of demand.

- No Arbitrage: Consumers should not be able to resell the product or service to other consumers.

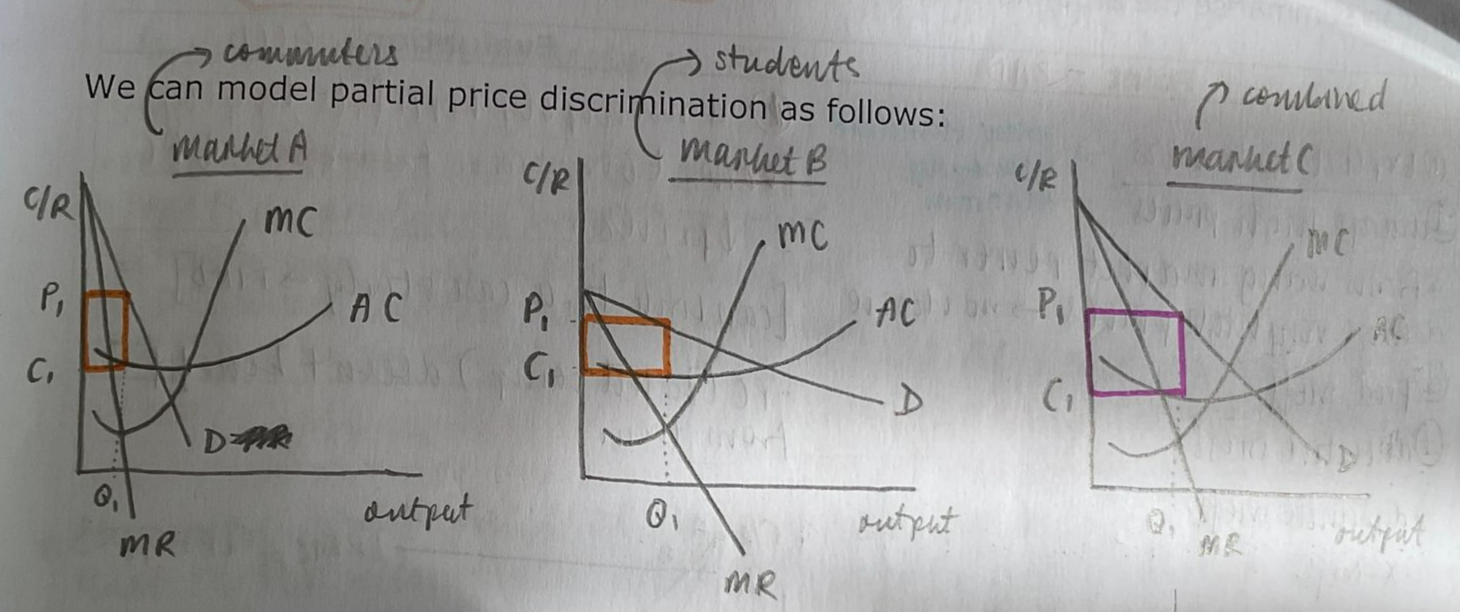

Diagram: Third-Degree Price Discrimination

Consider a monopoly firm that can segment its market into two groups with different elasticities of demand.

- Market 1 (Inelastic Demand)

- Market 2 (Elastic Demand) Diagram Explanation:

Explanation:

- Separate Markets:

- Market 1: The firm charges a higher price (P1) in the market with inelastic demand (D1), where consumers are less sensitive to price changes.

- Market 2: The firm charges a lower price (P2) in the market with elastic demand (D2), where consumers are more sensitive to price changes.

- Marginal Revenue (MR) and Marginal Cost (MC):

- The firm produces where the marginal revenue (MR) equals the marginal cost (MC) in each market. This ensures profit maximization in both segmented markets.

- Combined Profits:

- By charging different prices in each market, the firm can increase its total profit compared to charging a single price. The area between the MR and MC curves represents the firm's profit in each market segment.

Conclusion:

Price discrimination allows a monopolist to capture more consumer surplus by tailoring prices to different segments of the market based on their willingness to pay. This strategy enhances the monopolist's profitability by extracting more value from consumers compared to uniform pricing.

4.2.9 Natural Monopoly

Key Characteristics:

- High Fixed Costs: Significant upfront investment is required, making it inefficient for multiple firms to enter the market.

- Economies of Scale: Average costs decrease as output increases, meaning the firm can produce at a lower average cost when operating at a large scale.

- Barriers to Entry: The high initial costs and the advantage of economies of scale create substantial barriers for new firms to enter the market.

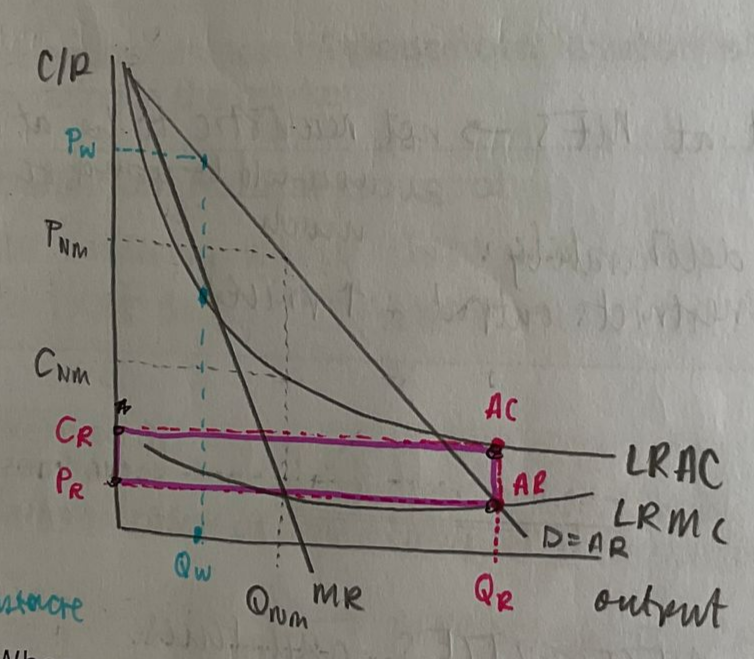

Diagram Explanation:

To illustrate a natural monopoly, we use a diagram showing the Average Cost (AC), Marginal Cost (MC), and Demand (D) curves.

- AC Curve: Downward sloping due to economies of scale.

- MC Curve: Typically below the AC curve and may be relatively flat.

- Demand Curve (D): Represents the market demand for the good or service.

Diagram:

Explanation of the Diagram:

- Average Cost (AC) Curve: The AC curve slopes downward, indicating that as the quantity increases, the average cost of production decreases. This reflects the economies of scale enjoyed by the natural monopoly.

- Marginal Cost (MC) Curve: The MC curve lies below the AC curve, typically flat or gently sloping upward, showing that the cost of producing one additional unit is relatively constant or increases slightly.

- Demand (D) Curve: The downward-sloping demand curve indicates the relationship between price and quantity demanded in the market.

Natural Monopoly Equilibrium:

In a natural monopoly:

- The firm can produce at a lower average cost over a wide range of outputs due to economies of scale.

- If the market were to be served by multiple firms, each firm would have higher average costs due to the inability to fully exploit economies of scale.

- Therefore, a single firm (the natural monopolist) can supply the entire market at a lower cost per unit than multiple firms could.

Regulatory Considerations:

- Unregulated Monopoly Pricing: The monopolist may set prices higher than the marginal cost to maximize profits, potentially leading to allocative inefficiency and consumer exploitation.

- Regulated Pricing: Governments may regulate natural monopolies to ensure prices are closer to the marginal cost, preventing excessive profits and protecting consumers. In conclusion, a natural monopoly exists when a single firm can supply the entire market at a lower average cost than any combination of multiple firms, primarily due to significant economies of scale.

500K+ Students Use These Powerful Tools to Master Monopoly For their A-Level Exams.

Enhance your understanding with flashcards, quizzes, and exams—designed to help you grasp key concepts, reinforce learning, and master any topic with confidence!

50 flashcards

Flashcards on Monopoly

Revise key concepts with interactive flashcards.

Try Economics A Flashcards5 quizzes

Quizzes on Monopoly

Test your knowledge with fun and engaging quizzes.

Try Economics A Quizzes29 questions

Exam questions on Monopoly

Boost your confidence with real exam questions.

Try Economics A Questions27 exams created

Exam Builder on Monopoly

Create custom exams across topics for better practice!

Try Economics A exam builder21 papers

Past Papers on Monopoly

Practice past papers to reinforce exam experience.

Try Economics A Past PapersOther Revision Notes related to Monopoly you should explore

Discover More Revision Notes Related to Monopoly to Deepen Your Understanding and Improve Your Mastery