Photo AI

Last Updated Sep 26, 2025

FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations Simplified Revision Notes for Leaving Cert History

Revision notes with simplified explanations to understand FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations quickly and effectively.

333+ students studying

FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Fianna Fáil Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

- During the 1932 election, Éamon de Valera promised to dismantle the Treaty that tied Ireland to Britain. This led to tense relations between the two countries when de Valera took power.

- Determined to take control of negotiations with Britain, he kept the role of Minister for External Affairs for himself.

- De Valera aimed to change Anglo-Irish relations, focusing on reducing British influence over Ireland.

- Foreign PolicyUpon taking office, de Valera retained Joseph Walshe as the Secretary of the Department of External Affairs.

- Walshe, who had served under the previous government, was a trusted and experienced figure. De Valera valued Walshe's advice, especially since he did not discuss foreign policy with his entire Cabinet. This continuity in leadership helped de Valera implement his foreign policy goals effectively.

- In 1933, the Department of External Affairs was given a budget of £85,000. Over half of this was spent on appointing diplomats to key countries, including the United States, Germany, France, and the Vatican.

- These appointments were crucial in asserting Ireland's independence on the international stage and were part of de Valera's broader strategy to distance Ireland from Britain.

The League of Nations

- Cumann na nGaedheal had secured Ireland's place on the Council of the League of Nations, an international organisation similar to today's United Nations.

- Ireland was scheduled to take over the Presidency in September 1932, shortly after de Valera took office.

- Although de Valera initially opposed the League, he quickly became one of its most vocal supporters, seeing it as a way to bolster Irish sovereignty.

- In his 1932 address to the League, de Valera strongly criticised the Treaty and outlined his plans for dismantling it, making it clear that Ireland would no longer be subservient to Britain.

- He also expressed concern about global issues, including the rise of Hitler in Germany and the potential for war in Europe.

- His speeches at the League helped solidify his reputation as a major international figure.

Anglo-Irish Relations

- Anglo-Irish relations were the core focus of de Valera's foreign policy. He wanted to remove as much British influence from Irish affairs as possible while still maintaining a peaceful relationship.

- One of his first moves was to take control of the Governor General's position, the representative of the British Crown in Ireland, reducing its significance and influence. This was part of a broader strategy to make Ireland more independent.

- De Valera was initially hopeful that friendlier relations could resume once he had established his government's authority.

- However, tensions remained high, particularly over issues like the land annuities—payments that Irish farmers were still making to Britain for land they had bought from British landlords before independence.

- De Valera's refusal to pay these annuities led to an Economic War with Britain, which involved both countries imposing tariffs on each other's goods.

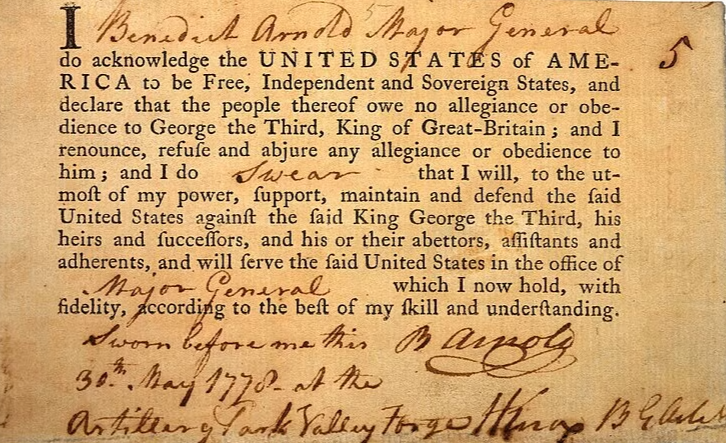

The Oath of Allegiance: 1932-1933

- One of the most contentious issues from the Treaty debates was the oath of allegiance that Irish parliamentarians were required to swear to the British Crown.

- Many anti-Treaty politicians, including those now in Fianna Fáil, had refused to take the oath during the Civil War.

- Upon taking power in 1932, de Valera made it clear to the British government that he intended to remove the oath, viewing it as an intolerable burden.

- To achieve this, de Valera introduced the Constitution Bill in 1933, which sought to abolish the oath.

- Despite British protests and resistance from the Irish Senate, de Valera pushed the bill through the Dáil (Irish Parliament). By 1934, the Senate, which had opposed many of his reforms, was also abolished.

The Governor General: 1932-1937

- De Valera also moved to diminish the role of the Governor General, the British monarch's representative in Ireland. James McNeill, the Governor General at the time, was an Irishman but still symbolised British authority.

- De Valera began by advising McNeill not to attend public functions, particularly those related to the Eucharistic Congress, a major Catholic event. McNeill resisted, leading to tensions with the government.

- On 9 September 1932, de Valera advised McNeill to resign, and after some resistance, McNeill did so. De Valera then appointed Domhnall Ua Buachalla, a former Sinn Féin TD, as the new Governor General.

- Ua Buachalla took little interest in the position, living modestly and reducing the Governor General's role to a mere formality. This diminished the office's influence, and de Valera eventually abolished it entirely a few years later.

Domhnall Ua Buachalla

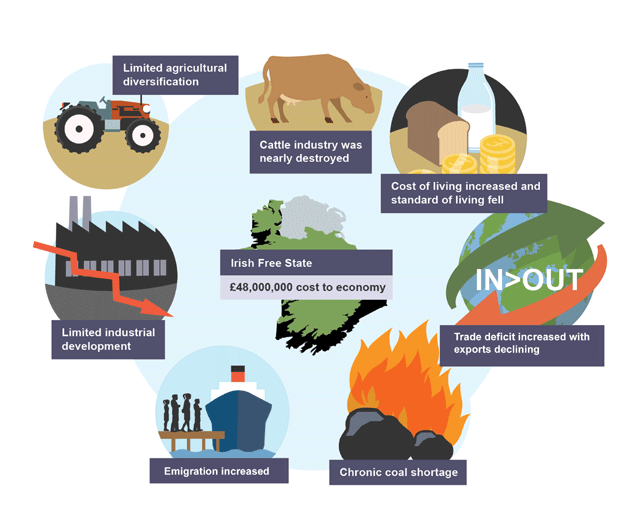

The Economic War

- In July 1932, de Valera escalated tensions with Britain by withholding £1.5 million in annuities that were due to be paid under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

- Irish farmers were paying this money as part of land purchases from British landlords. When de Valera announced the decision, Britain responded angrily, imposing tariffs on Irish exports, leading to a trade war known as the Economic War.

- This trade conflict hurt the Irish economy, particularly the agricultural sector, but it also rallied domestic support around de Valera.

- Despite the economic hardships, Fianna Fáil used this period to strengthen Ireland's economic independence, promoting self-sufficiency and reducing reliance on British imports.

- The Economic War continued until a settlement was reached in 1938, but it played a significant role in defining Fianna Fáil's nationalist stance and solidifying de Valera's support base.

The Privy Council 1935

- Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, decisions made by Irish courts could be appealed to the British Privy Council in London.

- De Valera saw this as undermining Irish independence and was determined to end the practice. In 1935, the Privy Council ruled against de Valera in a case which led him to introduce legislation to abolish its role in Irish affairs.

- This move was another step in de Valera's strategy to dismantle the remaining elements of British control over Ireland.

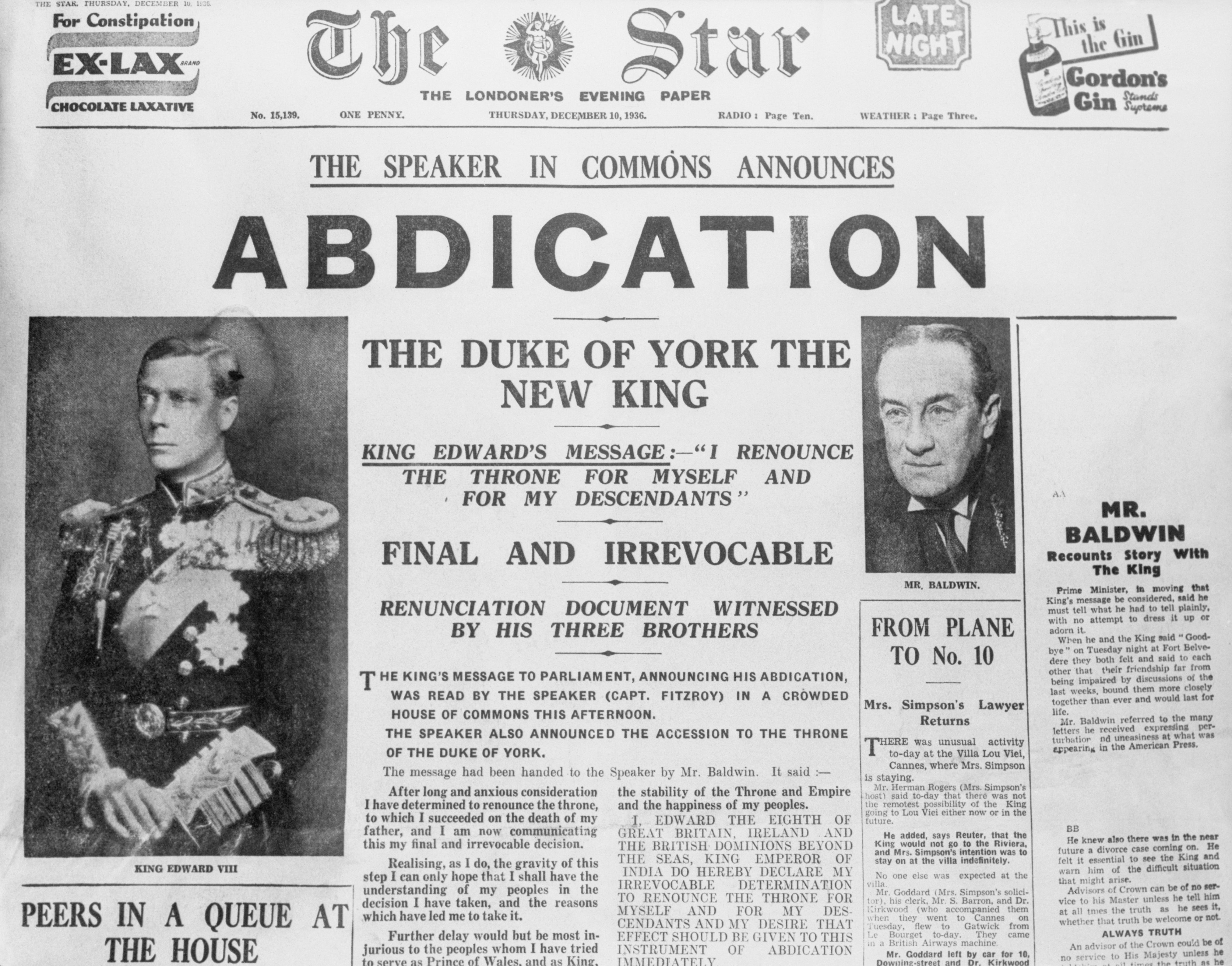

The Abdication Crisis in England

- By 1936, de Valera had significantly reduced British influence in Ireland, but events in Britain gave him an unexpected opportunity to go even further.

- That year, King Edward VIII faced a constitutional crisis over his decision to marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcée.

- The British government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, pressured Edward to choose between the throne and marriage. When Edward chose to abdicate, de Valera seized the moment to push for greater Irish independence.

- De Valera introduced two key pieces of legislation: the Constitutional Amendment Act and the External Relations Act.

- The first Act removed all references to the King or his representative from the Irish Constitution, while the External Relations Act reduced the King's role in Irish foreign affairs to a purely symbolic one.

- This move effectively completed de Valera's long-term goal of making Ireland a fully independent republic in all but name.

Anglo-Irish Agreement 1938

- Negotiations between Britain and Ireland continued throughout the 1930s, and by 1938, both sides were eager to resolve outstanding issues, including the Economic War.

- Talks opened in London on 17 January 1938, with de Valera leading the Irish delegation. By April, the two countries had reached an agreement on several key points, including Ireland's payment of a one-off £10 million settlement to end the land annuities dispute.

- The agreement also returned control of three strategic naval ports—Lough Swilly, Berehaven, and Cobh—to Ireland, which Britain retained under the Treaty's terms.

- This was seen as a major victory for de Valera, as it gave Ireland full control over its coastal defences, further reducing British influence.

- However, de Valera viewed the talks as only a partial success, as the issue of Northern Ireland's partition remained unresolved.

- By 1939, de Valera had largely achieved his goal of extending Irish sovereignty by dismantling the Treaty.

- While Ireland maintained a nominal link to the British Commonwealth through the External Relations Act, it was now effectively a fully sovereign state.

- This diplomatic achievement was later reinforced when Britain accepted Ireland's neutrality during World War II, marking the final recognition of Ireland's independence.

500K+ Students Use These Powerful Tools to Master FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations For their Leaving Cert Exams.

Enhance your understanding with flashcards, quizzes, and exams—designed to help you grasp key concepts, reinforce learning, and master any topic with confidence!

284 flashcards

Flashcards on FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Revise key concepts with interactive flashcards.

Try History Flashcards36 quizzes

Quizzes on FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Test your knowledge with fun and engaging quizzes.

Try History Quizzes29 questions

Exam questions on FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Boost your confidence with real exam questions.

Try History Questions27 exams created

Exam Builder on FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Create custom exams across topics for better practice!

Try History exam builder117 papers

Past Papers on FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations

Practice past papers to reinforce exam experience.

Try History Past PapersOther Revision Notes related to FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations you should explore

Discover More Revision Notes Related to FF Foreign Policy and Anglo-Irish Relations to Deepen Your Understanding and Improve Your Mastery

96%

114 rated

Fianna Fail in Government (1932-39)

The 1933 Election and Fianna Fail's Approach to Key Policies

243+ studying

182KViews96%

114 rated

Fianna Fail in Government (1932-39)

The Blueshirts and the Establishment of Fine Gael

286+ studying

200KViews96%

114 rated

Fianna Fail in Government (1932-39)

FF and the Economy - Key Details

227+ studying

190KViews96%

114 rated

Fianna Fail in Government (1932-39)

FF and the Economy - An Assessment

496+ studying

188KViews