Photo AI

Last Updated Sep 27, 2025

The Emergence of the North Simplified Revision Notes for Leaving Cert History

Revision notes with simplified explanations to understand The Emergence of the North quickly and effectively.

403+ students studying

The Emergence of the North

Before we jump into the more detailed political and economic side of Northern Irish history, it is important to lay contextual groundwork that will inform you of how a lot of the tensions in Northern Ireland came to be. Below are some key notes on how Northern Ireland was run from 1920-1945, detailing key acts, groups, and events that shaped the future of the island.

The Partition of Ireland and the Government of Ireland Act

-

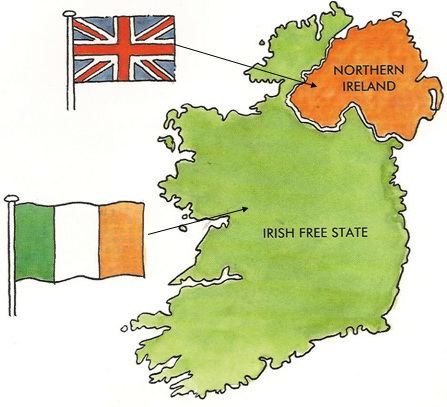

The Partition of Ireland was solidified by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, a crucial piece of British legislation that established two separate political entities on the island: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland.

-

This Act was Britain's attempt to address the growing demand for Irish self-governance while balancing the conflicting interests of Irish nationalists and unionists.

-

The Act ultimately resulted in the creation of Northern Ireland, comprising six counties of Ulster (Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh, and Tyrone), where the majority population was Protestant and unionist.

-

Northern Ireland was granted its own Parliament and a degree of autonomy over domestic affairs, with certain powers, such as foreign policy and defence, retained by Westminster.

-

The creation of the Northern Ireland Parliament marked a significant step in the region's political development, providing unionists with the self-government they desired within the United Kingdom.

- Sir James Craig became the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, leading the newly established government.

- The partition, however, entrenched sectarian divisions within Northern Ireland. The Protestant unionist majority viewed the new state as a triumph, securing their British identity, while the Catholic nationalist minority, who opposed the partition, felt alienated and disenfranchised.

- The Government of Ireland Act, instead of resolving tensions, laid the foundation for the social and political dynamics that would dominate Northern Ireland's early years.

- In the period leading up to 1945, Northern Ireland began to establish its identity as a distinct political entity within the UK.

- The creation of a separate parliament and government was a significant milestone in its development, though the sectarian nature of politics and the exclusion of the Catholic minority from power would have lasting repercussions on its social fabric.

Politics and the Economy in the New Northern Irish State

- In the early years following the creation of Northern Ireland, the political landscape was heavily dominated by the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), which held power continuously from 1921.

- This period saw the UUP firmly establishing its dominance over Northern Irish politics, a position it would maintain with little challenge until the mid-20th century.

- The UUP's control was reinforced by its strong support from the Protestant majority, which viewed the party as the guardian of their British identity and interests.

- The political environment was marked by the systemic exclusion of the Catholic nationalist minority, who faced discrimination in areas such as voting, employment, and housing.

- Gerrymandering was used to manipulate electoral boundaries, ensuring that unionist control was maintained even in areas with significant Catholic populations. This institutional bias contributed to the sense of alienation and disenfranchisement felt by the Catholic community.

- Economically, Northern Ireland experienced a mix of growth and challenges during the period leading up to 1945.

- The region's economy was heavily based on traditional industries such as shipbuilding, textiles, and engineering, with Belfast serving as the industrial heartland.

-

The shipyards of Belfast, in particular, were renowned globally, building some of the world's most famous ships, including the RMS Titanic.

-

The economy benefitted from its integration into the broader British economic system, which provided a stable market for Northern Irish goods.

-

However, this economic dependence on Britain also made Northern Ireland vulnerable to fluctuations in the wider UK economy.

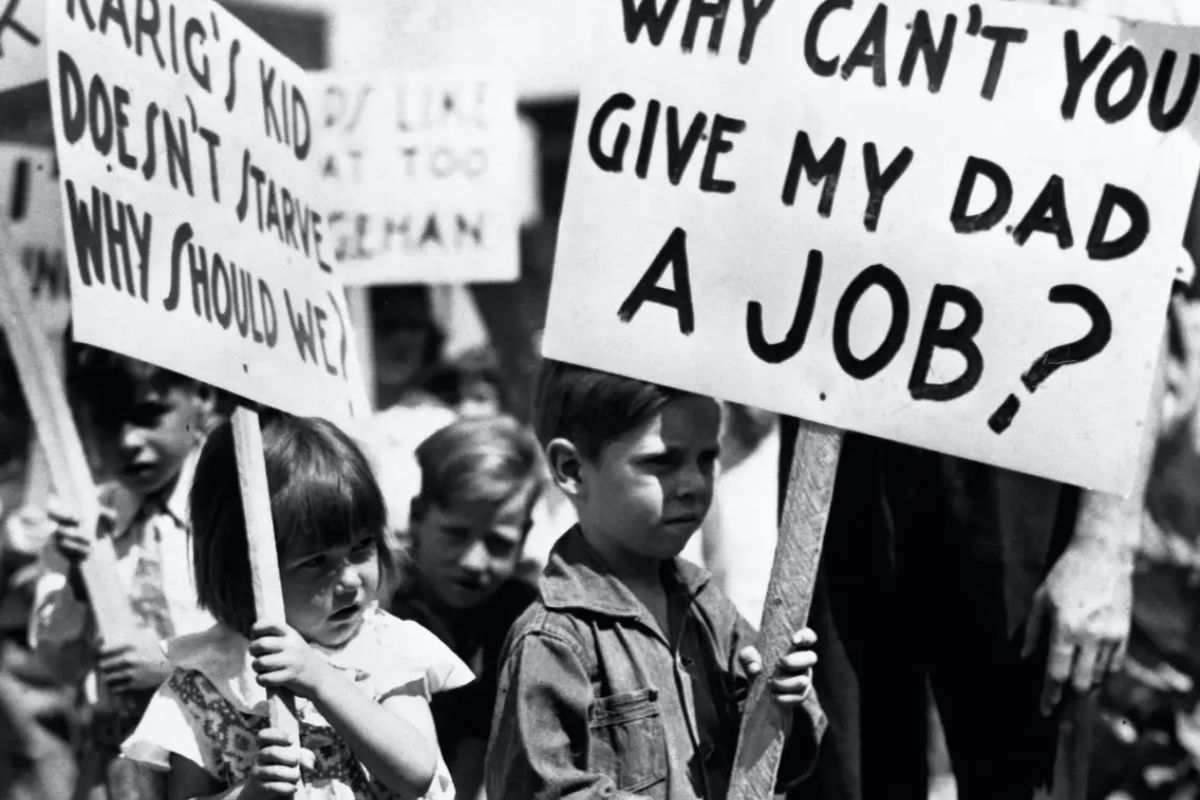

- The Great Depression of the 1930s, for example, hit the region hard, leading to high unemployment, particularly in industrial sectors. Despite these challenges, the Northern Irish government made some efforts to address economic issues, including initiatives to improve infrastructure and public services.

- The Great Depression of the 1930s, for example, hit the region hard, leading to high unemployment, particularly in industrial sectors. Despite these challenges, the Northern Irish government made some efforts to address economic issues, including initiatives to improve infrastructure and public services.

-

By 1945, Northern Ireland had begun to establish itself as a distinct entity within the United Kingdom, with a stable political system and a growing economy.

-

However, the persistent sectarian divide and economic inequalities between the Protestant majority and Catholic minority continued to shape the region's development.

-

The UUP's dominance ensured that Northern Ireland remained closely aligned with British interests, but the unresolved social tensions and economic disparities would lay the groundwork for future challenges in the decades to come.

Steps Taken to Protect Northern Interests

The Special Powers Act

-

The Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act, commonly known as the Special Powers Act, was passed by the Northern Ireland Parliament in 1922, just after the creation of Northern Ireland.

-

This law was intended to give the government extraordinary powers to maintain order during a time of significant unrest and violence, particularly related to the ongoing sectarian conflict between Protestants and Catholics.

- Under the Special Powers Act, the Northern Ireland government could arrest people without a warrant, detain them without trial, ban public meetings, censor newspapers, and even impose the death penalty for certain crimes.

- The act was controversial because it gave the government wide-ranging powers that were often used against the Catholic nationalist community, who were seen as a threat to the unionist-dominated state.

-

The Act was supposed to be temporary, but it was renewed several times and remained in force until 1973.

-

Critics argued that it was used to suppress political dissent and target the nationalist community, contributing to the deepening of sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland.

-

The Special Powers Act became a symbol of the discrimination and injustice felt by the Catholic minority, fuelling resentment and tension in the region.

The Establishment of the B-Specials

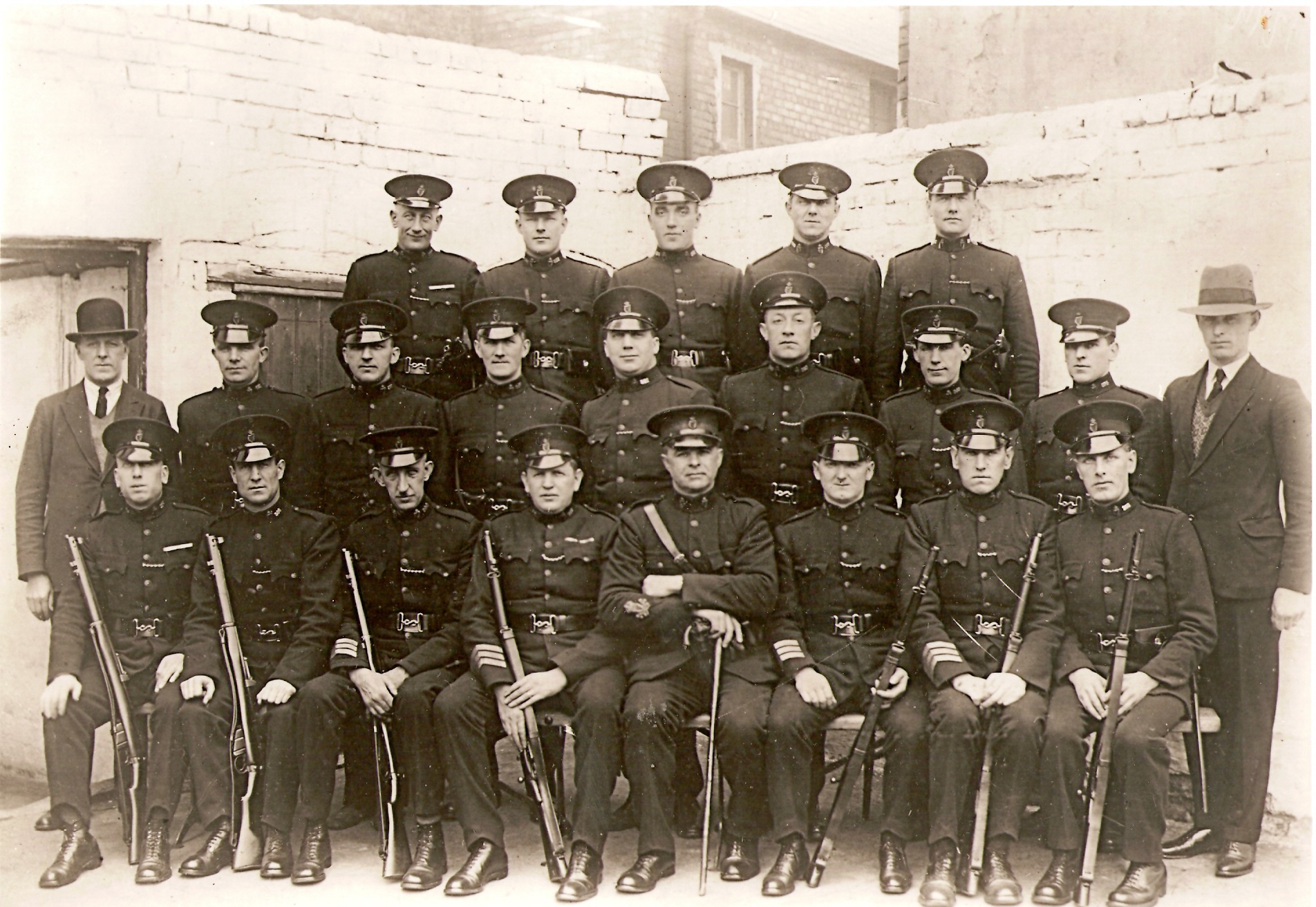

- The B-Specials, officially known as the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), were a reserve police force established in Northern Ireland in 1920, shortly before the partition of Ireland.

- The force was created to assist the regular police, known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), in maintaining order during a time of intense sectarian conflict and political violence.

- The B-Specials were made up almost entirely of Protestant men who were staunchly loyal to the unionist cause.

- They were armed and given wide-ranging powers to deal with any threats to the state, particularly from the Catholic nationalist community.

- The B-Specials quickly gained a reputation for being harsh and biased in their actions, often using excessive force against Catholics and nationalists.

- The establishment of the B-Specials was seen by many in the Catholic community as further evidence of the unionist government's discriminatory policies.

- The force was accused of deepening sectarian tensions and fostering an atmosphere of fear and mistrust.

- While the B-Specials were intended to protect the state, they became a highly divisive force in Northern Ireland, contributing to the growing resentment and alienation felt by the Catholic population.

- The B-Specials were eventually disbanded in 1970, but their legacy remained a source of controversy and bitterness in Northern Irish society.

The Abolition of Proportional Representation

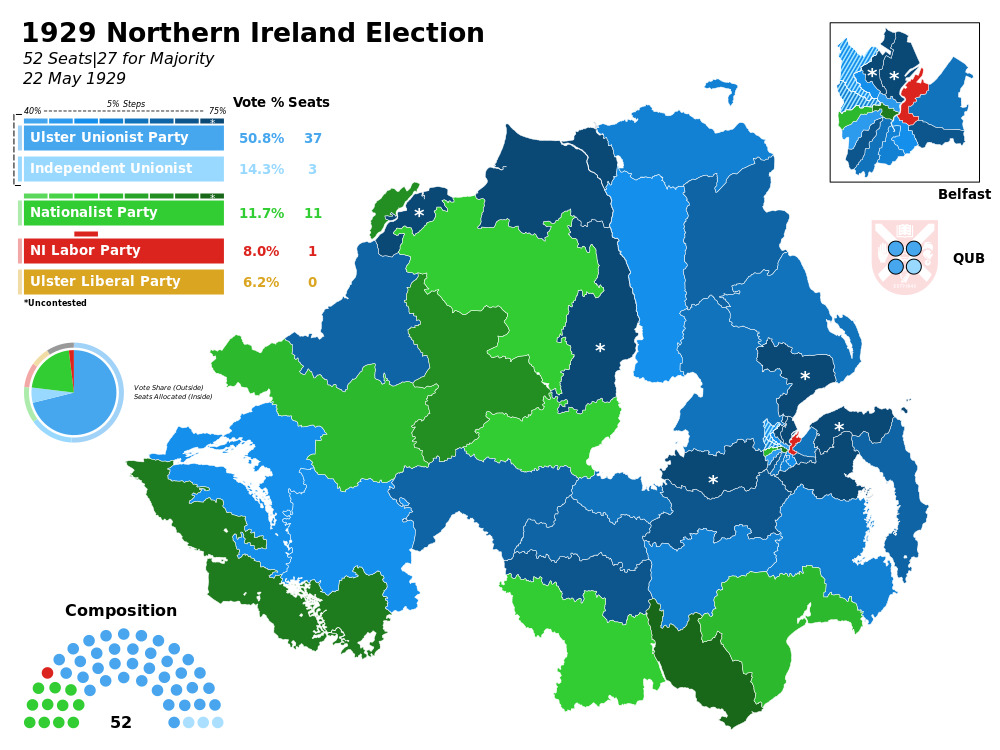

- The abolition of proportional representation (PR) in Northern Ireland was a significant political change that took place in 1929.

- Proportional representation was a voting system that aimed to ensure that the number of seats a party won in an election was proportional to the number of votes it received.

- This system was seen as fairer, especially in a society with deep divisions like Northern Ireland, where it allowed minority communities to have a voice in government.

- However, in 1929, the unionist government, led by the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), decided to abolish proportional representation for local elections and replace it with a first-past-the-post system.

- This change meant that the candidate with the most votes in each area would win, even if they did not have a majority.

- The abolition of PR was a strategic move by the UUP to consolidate its power and reduce the influence of the Catholic nationalist minority, who had been able to secure some representation under the proportional system.

- The result was that unionists became even more dominant in Northern Irish politics, while Catholics and nationalists found it increasingly difficult to win seats and have their voices heard.

- This move deepened the sense of political marginalisation among the Catholic community and contributed to the growing tensions and resentment that would eventually lead to the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

500K+ Students Use These Powerful Tools to Master The Emergence of the North For their Leaving Cert Exams.

Enhance your understanding with flashcards, quizzes, and exams—designed to help you grasp key concepts, reinforce learning, and master any topic with confidence!

60 flashcards

Flashcards on The Emergence of the North

Revise key concepts with interactive flashcards.

Try History Flashcards6 quizzes

Quizzes on The Emergence of the North

Test your knowledge with fun and engaging quizzes.

Try History Quizzes29 questions

Exam questions on The Emergence of the North

Boost your confidence with real exam questions.

Try History Questions27 exams created

Exam Builder on The Emergence of the North

Create custom exams across topics for better practice!

Try History exam builder117 papers

Past Papers on The Emergence of the North

Practice past papers to reinforce exam experience.

Try History Past PapersOther Revision Notes related to The Emergence of the North you should explore

Discover More Revision Notes Related to The Emergence of the North to Deepen Your Understanding and Improve Your Mastery

96%

114 rated

The Emergence of Northern Ireland (1920-45)

The Emergence of the North

209+ studying

199KViews